A private self-funded consortium including at least 12 truck operators of all sizes and four OEMs has formally launched Project Jolt, which is intended to “establish whether electric road freight transport can become commercially viable”.

The consortium is led by Prof David Cebon, head of the Centre for Sustainable Road Freight and a leading advocate of battery electric over hydrogen power for road freight.

Fleet operators, many of which already run eHGVs, will include John Lewis Partnership, Nestlé, William Jackson Food Group, Welch Group, Howard Tenens and Knowles Logistics. There will also be four SMEs and the net zero forum of the RHA is a member of the project.

“The fact is 70% of trucks in the UK are run by SME operators so it is very important to understand their specific issues,” said Cebon. “They carry out the most difficult logistics routes over long distances so they will need bigger batteries and their charging locations will be the most challenging in the UK. They also have an emphasis on flexibility as they need to be able to put their best vehicle on a job at any time.

“All of their trucks might well be 44 tonners and there are currently no BEV trucks with a long range that can pull 44 tonnes.”

The eHGVs will be used on a variety of route and load types and the idea is get drivers with a range of skills and experience to drive them, not just the best or specially trained drivers on the fleet. Cebon said that the detailed data collected from the vehicles would enable the impact of driver technique on vehicle range to be measured.

Project leaders acknowledge that, while many organisations have ambitious net zero targets, senior managers are unlikely to agree to a plan which costs more and is potentially less efficient than existing operations.

Cebon said: “We are sharing trucks and chargers on a three-month basis and testing a range of logistics operations. We are pooling the anonymised data to develop new sustainable models of working. By sharing the data in this way, we maximise the learning. By sharing the resources, we minimise the costs for everyone involved.”

He went on: “The vehicles and chargers do exist but the way we use them in commercial road transport operations has not been sorted out. It is a major challenge getting electricity to the vehicles when they are stopped anyway for a driver’s break or when loading and unloading.

“The transition to 100% electric road transport by 2035 or 2040 will be very challenging and it has to be done in a way that is financially viable.”

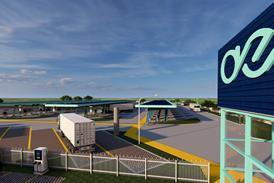

The difficulties in securing adequate power supplies means that the project is using three 350kW mobile chargers powered by diesel generators running on HVO that will be transported on a low loader between consortium members every three months.

Justin Laney, fleet manager at the John Lewis Partnership, said the portable chargers were expensive at £350,000 each but “will enable companies without a big enough electrical incomer to take part in the project”. John Lewis already runs electric Volvos and Laney added that having access to the mobile charger would enable him to test eHGVs on longer routes, possibly as far as Scotland.

He said that there was a “big question” over the range of the eHGVs and his experience with the Volvo was that it would do 200 miles comfortably on a charge.

Cebon said that a key question Project Jolt would seek to answer is where high capacity eHGV fast chargers should be located – in depots and warehouses where vehicles load and unload or on motorway services where drivers take breaks and overnight rest.

Data will be extracted from consortium members who are sharing leased trucks and chargers. A second source of data is “bring your own” eHGVs that are owned by some of the fleet operators.

The four 4x2 tractor units have been donated by Scania, Volvo, DAF and MAN for the duration of the programme. They are all plated at 42 tonnes and will come with the largest available battery packs of around 600kWh to maximise potential range. The project will measure the payload and time penalties associated with the extra weight and refuelling time of eHGVs.

Project Jolt is also looking at battery health and degradation. With the battery being a large weight and financial component of the truck, its performance will affect the residual value. Creating a secondary market will be crucial to the success of adopting eHGVs and the residual value will be largely determined by the value of the battery.

By modelling the industry using data gathered from consortium members, Project Jolt will be able to predict the impact of better batteries, faster warehouse charging, lower capital costs of trucks, improved driving techniques and potential legislation changes. The culmination of all of these is to establish whether eHGVs can deliver net zero cost increase in addition to net zero carbon emissions.

Project Jolt, which involves Cambridge and Heriot Watt universities, is a two-year programme that has already been running behind the scenes for a year. The first public results will be released this summer on the project’s website jolt.eco.

![Mercedes-Benz_eActros_600_(1)[1]](https://d2cohhpa0jt4tw.cloudfront.net/Pictures/274x183/8/1/8/17818_mercedesbenz_eactros_600_11_556244.jpg)