The Zemo Partnership held its 20th anniversary conference on Clean Air Day (June 15) at London City Hall.

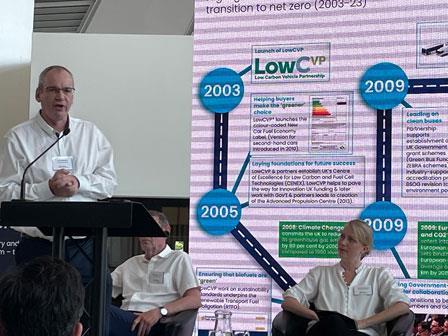

Zemo CEO Andy Eastlake (pictured) ran through some of the key achievements of the partnership – formed in 2003 as the Low Carbon Vehicle Partnership – over the last two decades and pointed out that while progress had been made in many areas, there remained much to do.

Twenty years ago the partnership said for example that fuel duty should be based on the carbon intensity of the fuel – but apart from a duty discount on natural gas over diesel this has still not been implemented. Zemo remains a strong advocate of renewable fuels as a way to help fleets cut carbon emissions from their diesel vehicles today rather than waiting for viable zero emission trucks.

HGVs are Zemo’s next sector to focus on after seeing good progress in the bus sector, which has benefited from direct and indirect subsidies to move more quickly to gas and now electric vehicles. Eastlake said the commercial vehicle sector seemed more “focused on incremental gains and step change has been slow to materialise”. He said that more trials such the DfT’s long-awaited ‘Zero emission road freight trial’ (Zerft) were key to paving the way for operators to adopt zero emissions vehicles.

Zerft is expected to put battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell electric trucks to the test to see which technology will be most suited to heavy long distance road freight transport – 20 years ago the LowCVP predicted that fuel cells would be “widely available in 10 years and electric vehicles would have a limited future use”.

That prediction has certainly not come true and, while arguments still rage over the role of fuel cells to extend the range and payload of battery electric HGVs, the cost of fuel cell technology is still even more prohibitive than pure battery electric.

While electric vehicle technology is progressing rapidly – at least for light commercials and smaller trucks – the lack of charging infrastructure remains a huge barrier to faster adoption by operators. “Electrification cannot happen without the infrastructure and this is still not fit for purpose,” Eastlake declared. “This will need a collaborative approach.”

But he remained optimistic that the government’s goal of the UK being net zero emissions by 2050 can be achieved. “We should celebrate the success from all our hard work,” he said. “Maybe together we can meet the zero emission target in the next 20 years.”

The scale of the challenge facing road transport over the next 27 years to become net zero was spelt out by Chris Stark, CEO of the Climate Change Committee (CCC) (below), which is just about to publish its latest annual review of the UK’s progress towards net zero.

Stark said that surface transport remained the biggest emitter of CO2, with cars and vans contributing the majority of those emissions. HGVs are not expected to decarbonise as quickly as light commercials but reductions in van emissions are way behind the schedule set by the CCC to decarbonise before the 2050 deadline.

“Surface transport needs to cut its emissions by 75% on 2019 levels by 2035,” said Stark. “That is ambitious but achievable.”

By 2035 the CCC’s target is for the HGV parc to cut its CO2 emission intensity to between 232 and 246 gCO2/km – a measure the industry has always rejected because it takes no account of the weight of freight carried.

Like Zemo, the CCC sees a role for renewable biofuels to reduce emissions from HGVs on the road to net zero but says there are two elements of government policy missing – scrappage schemes and road pricing. Road pricing is seen as politically unpopular but may be necessary to replace the £37bn revenue from fuel duty as sales of diesel declines.

“Questions about tax are fundamental and will be the big question for the next parliament,” said Stark. “Politicians have so far walked away from reform of the tax regime.”

Bob Moran, deputy director of decarbonisation strategy at the DfT, stood in for an absent minister and again did not announce the winning bidders for the £200m Zerft funding. But he pledged that in 20 years’ time “we will have decarbonisation sorted”.

In response to a question from David Cebon, director of the Centre for Sustainable Freight, about the cost effectiveness of hydrogen as a road fuel compared with batteries, Stark said there was a danger of hydrogen being seen as a “pariah” but argued that it will be needed. He warned that there would not be “unrestrained access” to renewable hydrogen but said its key benefit would be as a way of storing surplus renewable electricity from intermittent sources such as wind that would otherwise go to waste.

“We will need hydrogen in the industrial sector but its use in transport is a difficult question,” Stark said. “I don’t see it in light transport but there is a question over its role for HGVs. We will see what the market delivers and it is still seen as an option for heavier vehicles.”

Moran also pointed out that while an electric vehicle partly powered by a hydrogen fuel cell would be zero emissions, a hydrogen combustion engine would not and so would be banned along with other non-zero emission trucks after 2040. “The science says that is not a zero emission vehicle,” he said. “But it can be part of the transition.”

A panel discussion hosted by Andy Salter, MD of DVV Media International which publishes Motor Transport and Freight Carbon Zero, looked into the debate about pure battery electric versus hydrogen fuels cells in more detail.

Salter set the scene by pointing out that if the UK gets decarbonisation wrong and breaks the supply chain the economy would be “in a right mess”.

Peter Harris, vice president of international sustainability at UPS, agreed and argued that “as a country we need to make a decision on future technology”.

“Last mile electrification is happening but the big argument is about HGVs,” he went on. “This can’t be resolved by market forces alone.”

Gaynor Hartnell, chief executive of the Renewable Transport Fuel Association, said that more emphasis had to be put on the existing fleet of trucks as “they are emitting carbon now”, and claimed the “huge role” switching to low carbon fuels can play is “often overlooked”.

Kate Jennings, policy director of Logistics UK, said that while progress in the logistics sector had always been led by the private sector, the scale of the decarbonisation challenge was just too big for the industry to solve alone.

She agreed that operators “can reduce carbon emissions today with low carbon fuels – but the government does not recognise that”.

Cebon repeated his long-held view that battery electric was the best route to decarbonising road freight transport, probably even for heavy long haul trucks.

“Vehicles are going electric,” he said. “Long haul is the big question but they will also go electric because it will be a lot cheaper. All UK logistics can be done with electric vehicles. They are half the price of hydrogen vehicles and will get cheaper faster as the volume of batteries produced rises.”

But he conceded that the lack of charging infrastructure would be the biggest stumbling block, with operators waiting three or four years for grid connections to depots large enough to charge a fleet of electric trucks. “What will happen when we try to provide 15,000 warehouses with fat grid connections?” he asked.

He rejected the argument that batteries for HGVs would be too heavy, saying the “weight was the same as diesel” and that these battery packs would allow the vehicle to “drive for three or four hours” before needing to recharge. “We need to understand how this will work before we jump into putting lots of charging points into motorway services,” he said. “We can also use catenaries [overhead wires connected to trucks by pantographs] to reduce the size and cost of battery packs.”

Cebon criticised the delay in Zerft but said that the results wouldn’t be known until 2030 “when we already know the answer”.

“A partial solution is wrong,” he said. “We can’t have hydrogen for a small part of it – we can’t afford it.”

Jennings came to the defence of hydrogen, saying that it was already being use to power urban electric buses.

Salter then posed the question of what was the overall goal of government policy – decarbonisation or electrification?

Harris said that while the vision was net zero it was “important not to overlook the now” and to have short term milestones. UPS is electrifying its last mile fleet and using biofuels for its line haul trucks as an intermediate step toward full decarbonisation by 2050.

“We just have to get on with it otherwise if we hang around too long we can’t fix it in a decade,” he warned.

Hartnell was also all for getting something done now and argued that net zero was not the same as zero tailpipe emissions – an argument the DfT has yet to accept. She said there was a case to be made for “100% renewable fuels in the hardest areas to decarbonise”, a belief that many operators of 44-tonne and above trucks certainly share.

And while sales of new non-zero emission trucks will end in 2040, diesel vehicles bought before then aren’t going to disappear overnight. “Legacy vehicles will be around for a long time,” she pointed out. “If the government becomes too dogmatic something might fall apart and there is a risk that the policy will unravel.”

With most modern trucks able to operate on 100% biodiesel (B100) Hartnell also called for the Renewable Transport Fuel Obligation to be ramped up from the current B7 blend to B20 or B30. “There is no incentive to go to these higher blends,” she said.

Cebon conceded that while 90% of UK road transport could easily be electrified there might be a case for running the most difficult to decarbonise operations on fossil diesel as “biofuel will be needed in aviation and shipping”.

“The complete ban on internal combustion engines will need to be revisited,” he admitted.

Harris agreed, saying that the “numbers pointed to a broadly electric solution except in exceptional circumstances”. “Road transport will settle on electrification because the physics points to that being the most cost effective solution,” he said. “But it makes sense to use hydrogen as an energy buffer when there is surplus electricity.”