As part of the COP26 Glasgow climate conference, Scania used the official opening of its £10m flagship dealership and Scottish HQ at Eurocentral to the east of Glasgow to hold a one-day conference on 8 November to look at how the road freight transport industry can make the transition to net-zero carbon emissions.

As keynote speaker, Christian Levin, CEO and president of Scania and Traton, opened the event and set the scene while Andreas Follér, Scania’s global head of sustainability, set out the Swedish manufacturer’s strategy to make its trucks zero-emissions (read a full interview with Follér here) and Bob Moran, deputy director at the DfT, explained the government’s approach.

“COP26 is a serious thing, as science tells us that this is our last chance,” said Levin. “At Scania we decided back in 2016 that as we are part of the problem, we also need to be part of the solution. We decided our purpose was to drive the shift towards sustainable transport systems, and we have been doing a lot in the past five years.”

He said Scania now offered the largest range of renewable options available on the market today, including a range of rigid battery electric (BEV) and hybrid vehicles. He also revealed that by 2023 it would have 40-tonne BEVs on the road that would be capable of driving for four hours, and be fully charged within 45 minutes.

Levin said Scania is ready, willing and able to collaborate and engage with its customers, legislators and other stakeholders to strive to be 100% fossil-free by 2040. But he stressed that in addition to incentives to encourage widespread adoption of cleaner vehicles, it was vital that refuelling infrastructures for the various types of renewable fuels were introduced (see panel below).

This was something acknowledged by Moran, who told delegates: “We know we need to get it [alternative fuel infrastructures] right. We have to plan it. It can’t be left to just in time, and we have to get ahead of time on that.”

He thanked Scania for introducing cleaner vehicles, and for the role it will play in decarbonising road transport and helping the government achieve its net-zero transport plans.

Mike Hawes, CEO of the motor manufacturers’ association the SMMT, reminded the audience that under the government’s ‘Ten point plan for a green industrial revolution’ trucks between 3.5 tonnes and 26 tonnes must be zero emissions by 2035 and larger vehicles by 2040.

While the UK truck parc had grown just 5% to almost 590,000 in the ten years to 2020, the van fleet had shot up 30% to 4.6m, making it the “decade of the van”, according to Hawes.

“We have changed how we live and the high street has come to us,” he said.

In Q4 2020, sales of rigid trucks were down 3.5% and sales of artics fell 17.6%, leaving full-year HGV sales in 2020 on 33,000 units, 32% down on 2019 as a result of the pandemic and a worldwide shortage of computer chips, which Hawes said would take “a year or more” to resolve.

He added that “zero emissions commercial vehicles aren’t there yet” and sales of electric HGVs were “14 years behind” those of cars, partly because of a lack of recharging infrastructure.

“We will need 2,450 electric truck charging points by 2025 and 8,200 by 2030,” Hawes said. “We are nowhere near that and this will be the biggest obstacle to their adoption. It will need massive investment and we will need incentives for operators because these vehicles are much more expensive and the price of batteries will keep going up.”

Turning to the question of investment in electrical infrastructure, Graeme Cooper, head of future markets at National Grid, pointed out that the company owned and operated both the electricity and gas transmission networks so it was”technology agnostic” rather than favouring electricity.

“We are in transition and can’t wait because networks are a critical enabler,” Cooper said. “At one end is renewable electricity generation and at the other are consumers.”

He said people often asked if the grid can cope with a shift to EVs and the answer was a definite “yes”.

“Peak consumption was around 62GW back in 2002 and this fell to 30GW in the pandemic,” Cooper said. “On the road to net zero the UK will consume four times the energy so we will need four times the clean generation capacity and double the grid capacity.

“Transport is a smaller part of the transition than heating buildings but it is moving first.”

The transition will require 40GW of offshore wind generation and it has taken the UK 10 years to get to 10GW. “So we have nine years to get to 40GW and generation is ahead of the users of clean energy,” Cooper said. “We need double the grid capacity but where?”

When it comes to charging EVs it is a convenient fact that the National Grid high voltage transmission wires largely follow the UK’s motorway network, but significant extra capacity will be needed at the country’s 111 motorway service areas (MSAs).

“A typical MSA today has a 1MW connection,” said Cooper. “But it will need 7MW to 9MW to charge electric cars and could need 20MW to charge electric trucks – that is the same as a mid-size town.”

These upgrades will be partly paid for by the government’s £500m rapid charging fund created last year to ensure that there is a fast-charging network ready to meet the long-term demand for EV charge-points.

“With Project Rapid the government is intervening to future-proof grid capacity,” said Cooper. “But this is just for cars and National Grid has written to the transport minister to ask that if we put in infrastructure we do so for all vehicles not just cars. Do it right, do it once.”

This increase in electrical capacity along the UK’s major road network will be required whether zero-emissions trucks end up being powered by batteries, hydrogen or catenaries, as large quantities of clean electricity will be needed in any case. “It doesn’t matter – we will need a future-proofed, evenly spaced infrastructure,” he said. “We are waiting for the go and are hoping for a decision soon as it will take two to three years. We don’t have to pick the winning technology now – right product, right time, right fuel – but it will need big infrastructure.”

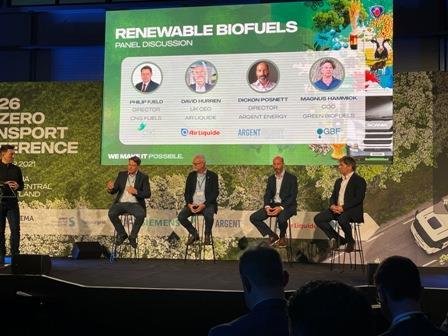

In the meantime, biofuels provide an immediate low carbon alternative to fossil fuel for trucks, and a panel of biodiesel and biomethane suppliers (pictured, top) made the case for operators to make the switch now while waiting for more widespread availability of electric trucks and charging infrastructure.

CNG Fuels supplies 100% biomethane that it claims already yields an 85% saving in CO2 emissions over fossil-derived methane and CEO and co-founder Philip Fjeld said that it would have nine public access refuelling stations operating by next year.

It aims to have 20 stations open by 2023 and is currently securing supplies of biomethane derived from animal manure that it expects to begin offering across all sites from next year at the same price as the fuel it currently supplies.

“When we switch to biomethane made from manure it will be a carbon-negative fuel,” Fjeld said. “We are being held back by lack of infrastructure and are working our socks off but it takes two to three years to open a refuelling station. Two years ago you could blame slow take up on the truck OEMs – now we are to blame.

“We want to build 12 stations per annum because right now operators are pulling more demand than we can supply.”

One of its major customers, the John Lewis Partnership, is converting its entire 500-strong fleet of trucks to biomethane by 2028.

Green Biofuels is a leading supplier of hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO), a drop-in replacement for diesel that reduces carbon emission by 90% with no need to modify the engine.

Magnus Hammick, COO of Green Biofuels, said his company’s product GD+ is readily available and with no infrastructure constraints is “an intermediate step while technology catches up”.

“One of our UK customers has become the first haulier to run 30m miles in the last three years with no fossil fuels,” he said. “We absolutely can supply our product and it is very low risk for operators to make the switch.”

Air Liquide is promoting the use of organic waste streams such as food waste and industrial residuals to produce biomethane which can either be put direct into vehicle tanks or injected into the gas grid to reduce the use of fossil-derived methane. UK CEO David Hurren said the company was seeing “triple digit” growth in demand for its bioLNG and 11 of its 20 UK stations were now delivering biomethane.

“We will open a new site in Avonmouth in the new year but it has taken 16 months to get planning consent,” he said. “Opening stations at operators’ depots is quicker though.”

Argent Energy is a pioneer of making biodiesel from waste products such as tallow, and director of corporate affairs Dickon Posnett pointed out that at present there are no tax or other incentives for operators to switch to renewable fuels. “Policy creates the market,” he said. “We react directly to legislation and at the moment there are no incentives to go to higher blends of biodiesel.”

The Renewable Transport Fuels Obligation currently requires a 7% blend of biodiesel (B7) in road fuel but Posnett said “we can easily go to B30.”

“One hitch has been warranty issues [with high blends of biodiesel] but Scania has addressed that,” he added. “Let’s get as much non-fossil fuel on the road as possible.

“We need to work closely with government because they don’t want to set a target and then miss it. But if they set a target we will invest to meet it.”

Hydrogen only for "niche applications", argues Scania CEO

Traton Group believes hydrogen will only be suitable for niche applications, and sees battery electric vehicles (BEV) as the future of long-haul transportation in Europe.

“I used to be an advocate of hydrogen, but have since changed my mind and am more sceptical and realistic,” said Christian Levin, president and CEO of Scania and CEO of Traton which owns Scania and MAN. He explained that the company has plenty of practical experience with the fuel, and is currently running hydrogen fuel cell trucks in Norway and Sweden.

“Our belief was that the fuel cell would be the answer, however one huge problem has emerged with these vehicles, and that is the energy inefficiency,” he said, adding that from a well-to-wheel perspective a BEV has an overall efficiency rate of 75%. This compares favourably with diesel, which is roughly 50%. With hydrogen, factoring in electrolysis, compression and liquefaction, transportation and filling, fuel cell and power generation, the overall efficiency rate is just 25%.

“So that means that the operating cost of a vehicle is three times higher [than BEV]. And to offset three times the fuel cost is very difficult for most customers,” he said. “We have gone into details thoroughly, and analysed segment by segment, application by application, market by market, and we see that the BEV in most applications will always beat the hydrogen vehicle on TCO. And that is the name of the game.”

Levin also highlighted the lack of green hydrogen available, and said that even when production increases, it’s likely to be purchased by chemical companies and the steel industry, who will be prepared to pay more for it.

“We agree [with Daimler and Volvo] on most things in the transition to clean energy, but on hydrogen we think they are really over optimistic,” he confirmed. “And we don’t think it is fair to tell governments around the world to invest in a hydrogen infrastructure alongside the battery electric infrastructure. We might be wrong, and they might be right, but that’s the standpoint of MAN and Scania.”

- Hydrogen is my favourite topic! Reread our interview with Christian Levin from 2019.